Western medicine is the standard approach to treating mental illness, addiction and trauma in Saskatchewan, but an Indigenous-run healing centre in Fort Qu’appelle is empowering its community to choose their own treatment.

Fort Qu’appelle’s White Raven Healing Centre operates out of the All Nations’ Healing Hospital (ANHH) and provides case-by-case support to people suffering from mental health issues and traumatic experiences. The WRHC uses Western healing practices facilitated through the hospital, combined with traditional Indigenous practices, such as storytelling, medicines, teachings and ceremonies.

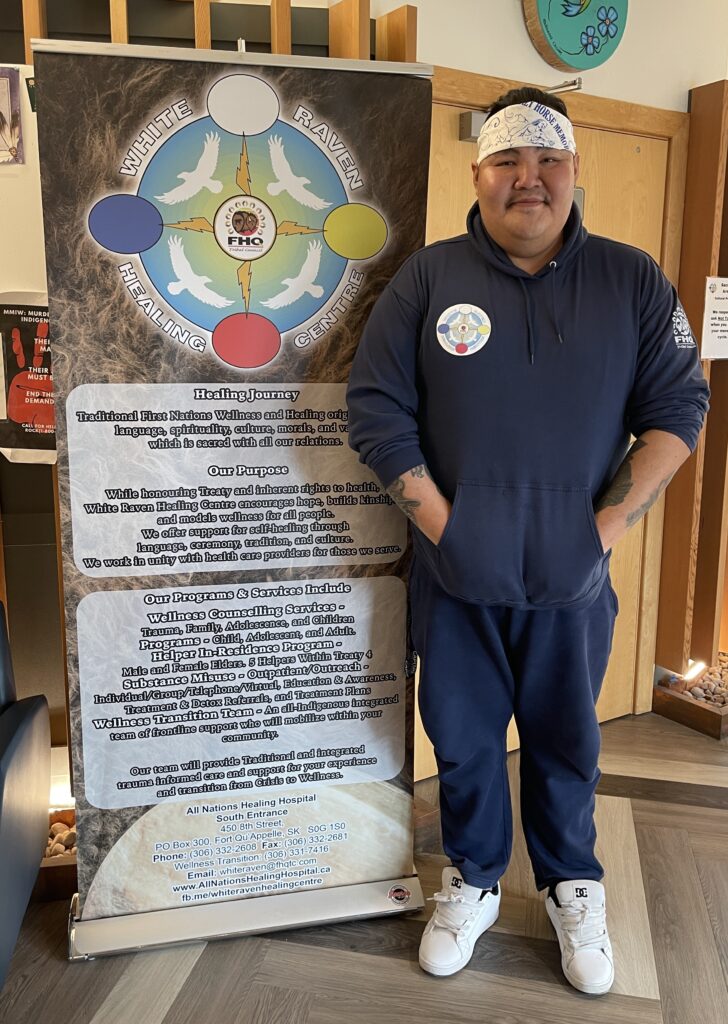

“It combines Westernized ways of healing, while also providing, if people wish to, holistic ways of healing,” said Mitchell Soo-Oyewaste, the Youth Wellness Program Coordinator at the WRHC.

“Allowing it to be a combination, not a conflict, but working together to provide the services for the nations that utilize it.”

It primarily serves the 11 First Nations of the File Hills Qu’appelle Tribal Council (FHQTC) by providing support through three teams: the Youth Wellness Team, Mental Health and Wellness Team and Cultural Wellness Team.

According to the FHQTC’s 2024-2025 Annual Report, there were 6,900 individual interactions that took place during presentations, workshops, and wellness days. Cultural Programming had 2,936 interactions; Mental Wellness had 2,203; Addictions had 418; and Missing & Murdered Indigenous Women had 417.

Other programs made up the remaining 926 interactions. These included health fairs, grief & loss counselling, Women’s Circle, Life Promotion, Responsible Gaming, support for Indian Residential School and Indian Day School survivors and CISM (Critical Incident Stress Management) training, which had 72 members trained in Level 1.

This year, there were 210 Indian Residential School survivors, 58 Indian Day School survivors, and 65 MMIWG2S+ family members that participated in these programs. However, these numbers only reflect those who chose to self-identify.

The Lebret Residential School, east of Fort Qu’appelle, operated from 1884-1998. “Each survivor has a different story. Who knows their stories? They do.” Said Don McLeod, Fort Qu’appelle’s Chief Administrative Officer.

“Some people have never recovered from it … it was a horrific time in our past.”

Staff at WRHC are Indigenous and vary in age. Some are elders with decades of healing experience, some are social workers, and many of them come from the communities that they serve.

“It’s someone familiar,” said Soo-Oyewaste. “So it’s not: ‘I’m going to counseling or a healing centre and I don’t know who’s there,’ but it’s ‘I know family there, or people I grew up with there, therefore I feel safe.’”

While WRHC prioritizes Indigenous people in the Qu’appelle region and the 11 nations in the FHQTC, programming is not exclusive. Soo-Oyewaste said that “other people have utilized the services, just because counselling is not as accessible.”

The WRHC doesn’t just operate in the hospital, but mobilizes staff to nations around Fort Qu’appelle to offer support for whatever a community might be facing.

With winter soon approaching, “This is an opportunity time right before what we call the ‘hard months,’” said Soo-Oyewaste. “… Because of isolation, the weather changes, and because there’s a lot of holidays … Those are the times that if you’ve lost loved ones, our Indigenous communities have the opportunity to provide those services if you need help.”

Fort Qu’appelle mayor Brian Strong sits on the hospital’s board and said that the WRHC is “received well throughout the community.”

“In smaller communities such as ours, most of the hospitals are closing. Here, because it’s Indigenous run, it’s not going anywhere,” said Strong. “We … work hand in hand with Treaty 4 on it. So it’s great. People come from Regina to go to the hospital here because it’s quicker service.”

The WRHC is hosting their Youth Wellness Day on Oct. 25 to promote awareness of both physical and mental health.

“If any of the youth think that they may need access to any of our services, and maybe they’re too shy or maybe no one said ‘we’re here,’ this is an opportunity,” said Soo-Oyewaste.